Full investigation on teacher turnover in Huntsville City Schools

Teacher Turnover

By Drew Pendergrass

A 2016 graduate of Huntsville High School, Drew Pendergrass was an editorfor the student newspaper “The Red and Blue.” He will be attending Harvard fall 2016. – drewpendergrass.com

Recently, I published this article on AL.com, concerning high rates of turnover among Huntsville’s teachers. The reaction has been unbelievable, with a variety of news organizations looking into the issues more deeply than ever before. However, this article was cut down from my original investigation for length. The original is printed here:

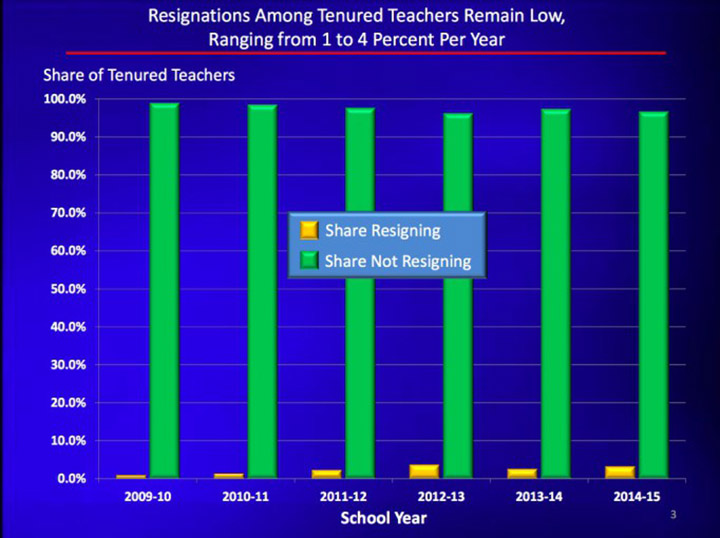

Over the winter break, seven teachers at Huntsville High School resigned or retired, on top of the nineteen who left over the summer. Since 2009, resignations of tenured teachers in the Huntsville City Schools system have risen 225%, as suggested by a graph provided by Superintendent Dr. Casey Wardynski in an August 2015 presentation entitled “Talent Management Update.” According to a report published by the Alabama School Connection, 20% of teachers in Huntsville City Schools have a year or less experience, putting it among the five worst districts in the state. Pat Miller, the Huntsville City Chapter President of the Alabama Education Association, a professional organization that represents teachers, calls this increase “unprecedented,” calling attention to the number of teachers leaving midyear.

I arrived at my 225% figure by counting the pixels on the yellow bars, and comparing the values. I asked Huntsville City Schools to confirm this number, but they neither confirmed nor denied this statistic. However, it reflects personnel records provided by the Alabama Education Association.

Huntsville City Schools Chief of Staff Johnny Giles said, “Reasons for individuals resigning are very personal in nature.” In any case, resignations of tenured teachers remain between one and four percent of the population per year in data available since 2009.

Historical data of teacher resignations and retirements from Huntsville High School are not available, so it is impossible to say how unusual these recent numbers are; however, students are noticing the change. Senior Edward Rosler said, “It just seems like more teachers are leaving,” noting recent churnings in the science department. Rosler’s geology teacher, Skot Holcombe, left mid-year, citing a realization that “teaching was not [his] passion,” while AP Physics teacher Athanasia Lianos and AP Biology teacher Elizabeth Simmons retired midyear.

When asked if teachers are leaving more often now than when he was a freshman, Huntsville High Senior Class President Ryan McGill said, “Yes, most definitely, especially the teachers that have been here the longest.” Scott Sharp, the former head football and softball coach as well as the AP Calculus teacher, resigned in June after eighteen years of teaching.

Sharp’s resignation in particular has led to criticism of district policy. A longstanding Huntsville City Schools rule allowed the children of teachers to attend school where they taught, regardless of the school for which the child was zoned. This changed recently in an effort to give all children in the school system the same access to the same schools throughout the district; as a result, children of teachers now must attend their normal neighborhood school. When asked about why he left, Sharp cited this new rule; his children are zoned for Buckhorn High School in the Madison County Schools system, about thirty minutes from Huntsville High. Sharp said, “With my wife’s health issues, I had an opportunity to teach where my children attend school, and also be closer to home.”

Pat Miller said of Sharp, “If we had an opportunity to keep a teacher of his caliber in the district, we should have. I hope we didn’t lose him over a policy.” Miller criticized the district’s gruffness in cases similar to Sharp’s, citing unreturned phone calls and emails; however, he was not active in this particular case. “We understand that the district has to make policies, and not all teacher requests can be granted,” Miller said, later qualifying: “If you can’t work out a deal, at least make the teacher feel valued.”

Adam Keller, a former teacher at Grissom and Johnson High Schools who now works full time for the AEA as Uniserv Director for District Two, where he represents Huntsville City Schools and Alabama A&M, said, “To the district, teachers are just numbers on a spreadsheet. And, quite frankly, so are the students.” The AEA feels that Huntsville City Schools has become less transparent and accessible, more bureaucratic and authoritarian, culminating in a system that is “unwilling to meet teacher’s requests.” Miller and Keller also cited the case of an award-winning elementary school teacher who left the district for similar reasons as Sharp, but for privacy reasons did not disclose her name.

Communication Problems

Another issue that has been cited by teachers is a sense of a negative school culture. Nicole Schwartz, the longtime newspaper sponsor who moved to Bob Jones High School in Madison City Schools before this year started, cited a “very positive environment for students and teachers” at Bob Jones as a reason behind her move. She also cited lower stress levels; in Madison City, she teaches 85 kids at a time instead of 175, receives a higher salary, and no longer has to handle the increased workload at Huntsville City Schools (her class workload was to increase to six per day from five).

Many teachers also feel that they are not being listened to. On the workplace review site Glassdoor.com, where Huntsville City Schools has a dismal 2.1/5 rating, one teacher said, “Administrators are out-of-touch and unsupportive. Communication is severely lacking. Teachers feel devalued and patronized…Teachers here are so passionate about their students. We try to advocate for what’s best for them, but no one is listening.” By comparison, Newark City Schools and Chicago City Schools, both of which have come under fire recently, have 3.0/5 and 2.8/5 ratings respectively on Glassdoor.

Adam Keller agrees that Huntsville City Schools has a culture problem, calling the climate since 2011 (when Wardynski took office) “authoritarian” and “unsupportive.” Pat Miller added that “teachers don’t feel supported or trusted.” Keller has also said that teachers will not speak out against perceived unfairness because, in his words, “teachers live in fear of retribution.”

When this article, originally written for the Huntsville High School newspaper, The Red and Blue, came up for printing, was pulled out of fear of possible retribution towards those involved with the paper’s publication. Concerns first arose after several teachers in the Huntsville High School English Department proofread the article and expressed worries about its reception among administrators. Regardless of whether any action would have been taken, these fears lead to the article’s removal. It is important to note that this article was written independently, and that any faculty at Huntsville High School are not responsible for its content.

In an incident in April 2012, Pam Hill, then a teacher at Hampton Cove Elementary School, addressed the board in the citizen comments portion of the meeting regarding the dramatic departure of her principal; in response, Dr. Casey Wardynski said, ” Principal McGhee was relieved for a whole host of reasons that where upheld in court. That had to do with poor leadership, ethical questions. And so we will relieve such leaders, we will relieve such teachers, and so I would caution you when talking to your employers to speak to them as your employers. The Board is your employer.” This was interpreted as a threat by some, including a local blogger and ardent opponent of the Superintendent, Russell Winn, who cited the incident as an example of “intimidat[ing] teachers into silence.” Dr. Wardynski did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

Several new district policies, like the required posting of “I can” statements, which phrase lesson objectives as statements starting with the words “I can,” and focus walls, where one wall of a classroom is painted a different color to attract students’ attention to the front of the class, have been met with responses from students and teachers ranging from lukewarm to mocking. When asked about the focus walls, Sophomore William Booth said, “It doesn’t really change the room that much for me,” and he “barely even looks at ‘I can’ statements,” a sentiment we found in most of the students we surveyed.

English teacher Julie Williams was supportive of I can statements, saying, “It may help the teacher more than it helps the kids.” Other teachers have complained about how they will be negatively evaluated if their “I can” statements are not posted. Miller said, “They are trying to make teacher evaluations as simple as checking off boxes.”

Williams said of focus walls: “I’m sure there’s some study that suggests kids are going to perform better.” When asked if she thought the district would have received less criticism if they would have provided this study along with the new painting plan, Williams replied, “I don’t think they care much about criticism,” adding, “I don’t think they have to justify why they’re painting.”

Keller was critical of this approach, and said, “They have to sell these policies to the teachers.” The Huntsville Chapter of the AEA says that a lack of communication between central office and teachers leads to a lack of understanding on both sides, whether on something as small as focus walls or as big as payroll. Aaron King, principal of Huntsville High, said, “Communication in any relationship, whether personal or in a school system, is the key to success.”

Discipline Policy

On April 21, 2015, the Judge Madeline Haikala handed down a consent order in the long-running Huntsville City Schools desegregation case, outlining a series of steps the school system would be required to take in order to reach unitary status, a legal state that means a school system has removed segregation to the greatest possible extent and can therefore operate with less federal scrutiny. Section VII of the consent order, which is concerned with student discipline, has led to changes in the Huntsville City Schools Code of Conduct that has created confusion and behavioral problems for teachers.

The consent order requires the district to “review class two and three offenses and reclassify offenses as lower level offenses, where possible, and/or eliminate the use of out-of-school suspension for these offenses,” and, by November 15 of every school year, report to the court “the total number and percentage of students receiving a disciplinary referral, disaggregated by race, in-school suspension, out-of-school suspension, expulsion, school referrals to law enforcement and alternative school placement.” However, some feel that Huntsville City Schools has been overzealous in meeting this requirement, leading to chaos in classrooms.

Between the 2014-15 school year and the 2015-16 school year, there have been major changes in the level of punishments of several common student offenses. Tardiness used to be a class one offense; now students must report late to class in “weekly incidents during a two month period of reporting” to be in violation of the code, according to the Code of Student Conduct found on the district website. Similarly, classroom disruptions now must take place over a period of two months to be an offense. Trespassing, cheating, and brief fights have also been lowered to class one offenses. AEA chapter president Pat Miller also cited that non-tenured teachers will be hurt in their evaluations for writing students up; however, the district claims this is not true. Gregory Hicks, Director of Behavioral Learning for Huntsville City Schools, did not comment on the discipline policy, although in faculty meetings he has said this policy is a work in progress according to teachers who were present.

The discipline section of the consent order came as a result of differences in punishments of students by race, which, according to the teachers we interviewed, is a prominent issue. “There really was a disparity in discipline for black students,” said Keller of the AEA, “and none of the teachers want to contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline.” However, he does not think Huntsville City Schools adequately addressed the issue. “[The district], instead of actually solving the problems, just took the most common offenses and made them unpunishable. This has led to chaos in classrooms,” said Keller.

Aaron King has taken note of these concerns, inviting Hicks to speak to Huntsville High teachers in a faculty meeting. In any case, according to Miller, the result of the new policy leads at best to teachers being “afraid to write anyone up,” and at worst to “dangerous classroom behavior.”

No Raise in Years

According to a report from the Alabama Education Connection, since 2007, teachers in Huntsville City Schools have not had a Cost of Living Adjustment. That, combined with increases in employee insurance and retirement contributions, means teachers are being paid less in real dollars today than they were ten years ago. Meanwhile, administrators have received a 4.6% raise each year; this pay raise is a Huntsville City Schools policy, not a state one. HCS pays its teachers a starting salary at the state minimum: $36,867 per year, less than Madison City or Madison County Schools, despite the district’s $30 million surplus and multiple six-figure administrative salaries.

However, Adam Keller denies that the salary stagnation is the reason teachers are leaving. In the words of Aaron King: “No one goes into education for the money.” Keller said, “A raise would be nice, but it won’t solve our morale issues.” Pat Miller cited salaries as a sign of a lack of appreciation, and said, “Pay shows that teachers are not a priority.”

Common Core, Testing, and District Pacing Guides

In 2002, the No Child Left Behind Act was signed into law. It was the first attempt by the federal government to hold schools accountable for their quality of teaching, and started as a bipartisan agreement to make our school system competitive internationally. Quickly, the agreement fell apart; students were assessed yearly, and if the student body did not show “adequate yearly progress,” schools would face sanctions. By 2014, 100 percent of students were to be proficient in English Language Arts (ELA) and Math, a goal that was seen as increasingly impossible as the year approached.

Common Core was an answer to what many on both sides of the aisle saw as federal overreach; if No Child Left Behind was characterized by tough love and force, Common Core is characterized by its intended flexibility and voluntary nature. Unlike No Child Left Behind and its weaker successor, the Every Student Succeeds Act (signed into law in December 2015), Common Core is voluntary and state-driven; Alabama adopted the standards in 2010.

Contrary to popular belief, Common Core does not set forth any specific curriculum; instead, it provides a series of benchmarks that every student should understand, and sought to replace the state-specific No Child Left Behind tests with national tests that measured critical thinking instead of rote learning. This, combined with the relatively lax nature of the Every Student Succeeds Act, was intended to relieve the pressure of No Child Left Behind and put education back in state control, while still keeping standards high.

However, the voluntary nature of Common Core was undermined to a certain degree by Race to the Top. The Obama administration program gave states a chance to compete for $4.35 billion in federal money, earmarked for those that adopted national standards, with extra cash given to states that tracked student development from early education to high school graduation. This program, which started in the heat of the Great Recession, has been criticized for forcing school to adopt standards quickly in hopes of alleviating their cash-strapped budgets.

As a result of the Obama administration’s support, the influence of billionaire education activists like Bill and Melinda Gates and George Soros, and the soaring profits of testing and education companies like Pearson, Common Core has received a huge backlash from conservatives and liberals alike. The standards have made deficiencies in tougher-to-measure areas like critical thinking clear, exposing lacking elements in schools that had passed muster in the No Child Left Behind era (schools like Huntsville High School). Former Secretary of Education Arne Duncan outraged many with his comments that “some of the pushback” from Common Core is coming from “white suburban moms” who realize “their child isn’t as brilliant as they thought they were, and their school isn’t quite as good as they thought [it was], and that’s pretty scary.”

While Common Core and national standards for education will likely remain a topic of debate for years, the results of its implementation are clear: Teachers now have much less flexibility in their classes. In addition to adopting the Common Core standards mandated by the state, Huntsville City Schools has adopted ACT’s QualityCore system. According to ACT’s website, QualityCore “aligns well” with Common Core standards, while providing “greater level of detail than the ACT College and Career Readiness Standards” for individual courses. However, because QualityCore is designed to align with both ACT guidelines and national standards, it is a particularly rigorous program.

The result of adopting QualityCore, in addition to the already-difficult Common Core, is a strict pacing guide for the district; teachers are given a set number of days to meet objectives for different content areas. This has triggered complaints from many teachers. Adam Keller of the AEA said that quarterly district benchmark testing, which measures mastery of QualityCore and Common Core objectives that should have been learned if the pacing guide was followed, has led to a loss of classroom control: “Licensed professionals lose their autonomy as a result [of testing].” Pat Miller added, “Bottom line: teachers have less control over their work today than ever before.”

With the fast implementation of these lofty standards, our school system had to make a decision: either more kids will fail and repeat grades, or kids will be shuffled through without actually meeting standards. Our system, like many across the country, appears to have chosen the latter. Despite standards being higher than ever, so are high school graduation rates. Some of this increase in graduation rates has come as a result of low teen pregnancies, as well as groups that identify and help failing or chronically absent students. However, critics argue that many students are still unprepared for many jobs that formerly could be had from just a high school diploma, such as manufacturing. In order to graduate, students used to be required to pass the Alabama High School Graduation exam; however, since the class of 2014, this is no longer required.

As a part of the consent order, Huntsville City Schools implemented a new district-wide grading policy. Student grades are all weighted as sixty percent from tests, thirty percent from quizzes and in-class work, and ten percent from homework, regardless of the course. In addition, students no longer receive zeros for work not turned in – they receive a one. Students all have an opportunity to make up failed tests for a grade up to a seventy; late work must be taken as well, with points taken off each day the work is late. This policy has received criticism, particularly from teachers in demanding courses.

After a student in her Algebra II class did not understand what a cube root was, Krystle Johnson, a math teacher and basketball coach, said, “I’m not sure how some of these kids made it to me. They’re missing something in middle school.” Johnson cited the ability of all students to retake failed tests for a grade up to a seventy as a possible reason for unmerited promotion to her level of math. A teacher who wished to remain anonymous added that “teachers at Huntsville City Schools are afraid to fail students.” A Huntsville City Schools teacher on the online workplace review site Glassdoor.com said that the new district-wide grading policy “enables apathy and increases work for teachers,” because teachers have to stay after school and sometimes write new questions to allow students to retake failed tests.

Because there is so much material to cover, teachers feel it is impossible to answer questions students ask outside the scope of the class, even though those questions are sometimes necessary for understanding the present material. One teacher mentioned that they “feel like [they] have to meet the benchmark timing, even though the kids are behind.” The grading policy was mentioned as a part of this problem; a different teacher reviewer on Glassdoor mentioned that there was “too much pressure on teachers to make student grades fit what is expected by supervision, regardless of how students behave in a class, or how students actually prepared and performed in some classes.”

Controversial State Legislature

For the Alabama legislative session starting February 2, Senate President Pro Tem Del Marsh proposed his controversial RAISE Act bill, which dramatically alters the tenure system in Alabama. According to an initial draft, starting in 2017, new teacher hires will have two choices: a non-tenured performance based career track with higher pay, but low security; and a traditional tenure track, where teachers will be paid less. The bill also increases the years a teacher must work to get tenure from three to five years; support staff are no longer eligible for tenure, nor are teachers that score too low on the new teacher evaluation system proposed by the bill. Existing tenure can also be revoked if a teacher scores poorly on two consecutive performance ratings. Cost of Living adjustments for tenure-track teachers are capped at five percent per year. For principals and assistant principals, evaluations are largely based on “evidence of growth in student achievement;” starting in 2022, forty-five percent of their evaluations will be based on these measures of student growth.

A new draft of this bill reportedly eliminates the tenure track for teachers hired after 2017.

Cliff Pate, an AP Statistics teacher at Huntsville High, has criticized the bill’s practicality; he said, “Whenever you tie pay to test scores, you get people who are teaching to the test, which is always bad news when you want to get kids to learn for the love of learning.” Pate thinks a lot of teachers will take the performance track at first, should there be a choice, because “it’s been so long since we’ve had raises…they’ll see that as their only path towards making more money.” However, he says the performance track won’t last, because, in his words, “Teachers just want some level of respect. We don’t want to be rich or famous or anything.”

In a letter published on AL.com, a group of teachers also raised the point that classes without testing, such as art and music, will be difficult to evaluate on the performance track proposed by Marsh.

A spokesperson for Marsh could not be reached for comment. The bill has not yet been passed, but past education bills from Marsh, including a charter school bill, have been made into law.

The Future of Public Education in Huntsville

Teachers are worried about the future, which has contributed to low morale in systems across the nation. New national reforms, paired with controversial measures in performance pay and charter schools, as well as a case currently being heard in the Supreme Court about union fees, all have placed education in an uncertain place. Test scores and increased accountability have also dramatically changed the tone of education nationwide. Principal Aaron King said, “With No Child Left Behind, we went from a culture of trust to a culture of test scores.” This uncertainty and changing standards has frustrated AEA representative Adam Keller to the point where he said, “Public education is under attack in this country.” While this may be an overstatement, there is certainly some truth in it; in the words of King: “Education is in a state of revolution right now.”

However, prominent national issues do not hide the fact that Huntsville City Schools is partially to blame for teachers in the district leaving. A sense of disrespect felt by teachers is leading to real issues in morale, something noticed by students who are seeing their teachers leave. King said, “We have a shortage of teachers with five to ten years of experience, and we need that group to be a successful school.”